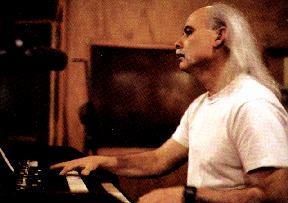

Jeff Palmer is a true innovator among modern jazz musicians who use the Hammond B-3 instrument. They learn their skills in relative isolation, unlike trumpet players or saxophonists. There is no saxophonist to copy and no army to share tips and tricks with. His talents as both an instrumentalist and composer combine to create a sound that’s both futuristic yet rooted in the history of jazz. Musicians like Palmer remind us that even in a world of sophisticated technology such as sampling, emulating and other high-tech gadgetry, there are still many sounds to be made by today’s machines. Palmer was born in Jackson Heights, New York on June 1, 1948. From the beginning, music was an integral part of Palmer’s life. His father, a professional guitarist, was born in Sicily. At the age of 4, Palmer was already playing the accordion and was earning a living performing at the piano. At the age of 13, Palmer was introduced to the future by listening to an album by Jimmy Smith. Smith is widely considered the greatest jazz organist ever. The Hammond organ was the first thing that Palmer fell in love with. Palmer received his first Hammond organ for his 15th Birthday. He packed up his squeeze-box and moved on. Palmer, like most jazz organists was a solo player when it came time to learn how to play the instrument. Palmer began to work as a sideman at small jazz clubs in the United States and Europe, gaining technical proficiency. Paul Bley, a pianist, was one of the performers who helped Palmer become a solo performer. Bley produced Palmer’s 1981 debut album, Outer Limit. This was a collection original pieces performed solo on the organ. This album may have been the first to record solo jazz organ originals. The album, which was released on the Improvising Artists record, was an organ masterpiece that took the Hammond into harmonic directions never before possible on the instrument. Palmer and Bley had a strong bond that allowed them to tour together in Europe twice each year. In the mid-1980s Palmer was leading a group that included guitarist John Abercrombie (a frequent collaborator for many years); drummer Adam Nussbaum and Gary Campbell on saxophone. In 1987, the group recorded Laser Wizard, which was nominated for a Grammy. Milo Fine, a Cadence magazine reviewer, saw Palmer’s work in the context of a historical chain of jazz fusion that also included Tony Williams’s Lifetime (which featured organist Larry Young) and John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra. Fine was impressed by how Palmer’s group flows and swirls with an eloquent assertiveness. Palmer and his company followed up Laser Wizard in 1987 with Abracadabra. It was not released on Soul Note until 1990. Palmer continued to explore the fusion territory he explored with the previous album, using the same lineup, except for Dave Liebman, the Miles Davis band saxophonist. Art Lange, Down Beafwriter, was not convinced. Lange compared Abracadabra to Miles Davis’s work nearly 20 years ago. He felt the quartet lacked direction and drive. He wrote that “often things flounder aimlessly” in his February 1991 review. In 1993, Palmer released the next album in his series of recordings with Abercrombie. On Ease On, Arthur Blythe played alto sax with Victor Lewis playing drums. Palmer’s compositions used traditional blues structures but went in surprising new directions. Ease On was praised by many critics. Ease On was praised by many critics. Pete Fallico, a jazz critic, wrote that Shades was a “ferocious Hammond organ blues” in a futuristic context. This album also featured Billy Pierce, tenor saxophonist, and Marvin “Smitty” Smith as drummers. Jazz Times magazine also noted Palmer’s compositions, calling them “memorable blues figures, very short but open-ended enough to drive hard-driving grooves,” and comparing them to Thelonious Monk’s. In 1996, Palmer returned with a new album. The project was called Island Universe and reunited Palmer with Arthur Blythe. This time, Rashied Ali performed the drumming, which is a pioneer in free-jazz percussion. Two reviewers, Scott Yanow for Cadence, and John Corbett, for Down Beat, both acknowledge that Palmer has moved beyond the shadows cast earlier by Smith and Young and is now charting his own course toward the future. Corbett also agreed with the earlier assertion that Palmer had a touch Monk influence in his compositional style. Fred Bouchard, the writer, went further and said that Palmer “indeed picks the hard cudgels, loomy pedals, and exploration areas of the B-3 where nobody has gone before, and sending back obscure messages.” He is concerned with the future in both his music and his assessment of music’s direction. Palmer has developed music school courses for jazz organ, which is an instrument that has been neglected by even the most prestigious academies. Palmer is a composer who believes innovation is his most important job. If a composer wants to be successful, he must let go of the existing music. Fallico wrote in 1996 Jazz Now that Palmer’s mission was to give audiences climaxes and he did it intuitively. He also said, “Jazz musicians are responsible for giving the audience a glimpse of the future [Audiences] need your blood and you must be good at it.” Source: www.encyclopedia.com