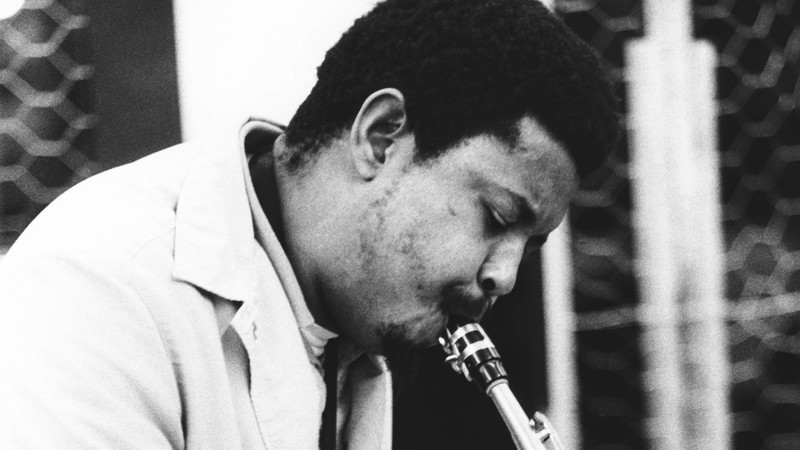

Bheki Mseleku fused elements of African township music with American bebop to become the most prominent South African jazz pianist of his time. He was born Bhekumuzi Hseleku in Durban on March 3, 1955. His father was a teacher of music. The elder Mseleku, a deeply religious man, was afraid that any of his seven children would choose a career as a professional musician. He kept the piano safe and eventually cut it up for firewood. Mseleku’s mom slipped the key to her husband when he was away. Over time, the boy learned how to play and even modified his style after a go cart accident that claimed two fingers. He also developed a faster and more efficient technique to compensate for his shorter hand span. Mseleku began playing the electric organ in his teens. He was a part of the semi-professional Expressions group. In 1975, he moved to Johannesburg to join hard bop band the Drive. He later co-founded the progressive jazz project Spirits Rejoice alongside bassist Sipho Gumede before signing on with multi-instrumentalist Philip Tabane in his popular group Malombo. Mseleku gained international attention when he performed with Malombo at 1977 Newport Jazz Festival. He met McCoy Tyner, his boyhood idol, and Alice Coltrane, the harpist, at the Newport Jazz Festival. She later gave Mseleku the mouthpiece that John Coltrane used during the sessions that produced the jazz classic A Love Supreme. Mseleku returned to Johannesburg to find its oppressive apartheid culture virtually unbearable, and after a brief tenure in Botswana where he supported trumpeter Hugh Masekela, he and percussionist/composer Eugene Skeef relocated to Stockholm. Mseleku did occasionally work with Don Cherry, an expatriate trumpeter, but he lived largely in Sweden, suffering from diabetes and other ailments. Mseleku moved to London in 1985. He was finally recognized and praised two years later when pianist Horace Silver offered him a two-week stay at the renowned jazz club Ronnie Scott’s. Scott was a quiet man who seldom spoke to the media. Scott called jazz critics to praise Mseleku’s performances. Mseleku often plays unaccompanied with his tenor saxophone (his other weapon of choice), and his deeply meditative, technically flawless sets quickly became a legend. This attracted jazz players Courtney Pine and Steve Williamson, who later appeared on Mseleku’s star-studded 1991 debut album Celebration. Mseleku was later diagnosed with bipolar disorder and fled London to seek refuge in a Buddhist temple. He lived for two years without any telephone or piano. This is why the album took so long. Mseleku was still a star after Celebration’s critical success. In 1992, Meditations, his second album, saw him release Meditations. It documents a live set at the annual Bath International Music Festival. He was also featured on ITV’s The South Bank Show that year. Mseleku gained international recognition and toured Europe, America, India, the Far East and India. He also participated in recording sessions that featured Pine, Sibongile Khumbalo and other South Africans. Timelessness, his third album on Verve, was released in 1994. It featured collaborations between Mseleku and American jazz legends Joe Henderson, Elvin Jones and Abbey Lincoln. Mseleku joined Henderson’s touring group, before heading to Los Angeles with Ornette Coleman’s rhythm section of Charlie Haden and Billy Higgins. Mseleku assembled a third, and final Verve album, 1997’s Beauty of Sunrise. This time, Jones and Coltrane were joined by Ravi, Jones’ son and saxophonist. He was based in Johannesburg again by this point, but the experience had a devastating effect on his mental health. Mseleku’s generousity quickly drained his major-label earnings. Robbers also stole his Coltrane mouthpiece. This loss remained with him for the rest of his life. Mseleku’s final album, Home at Last, was recorded in 2003. It featured local musicians. Although the album was praised by critics for being the best distillation of his unique aesthetic, it did not sell well at retail and Mseleku turned to teaching to make ends meet. In 2006, he returned to London to seek more steady work. However, his diabetes was limiting his ability to perform. Mseleku’s death on September 9th 2008 meant that a residency was already in place at Johannesburg’s club Bassline.