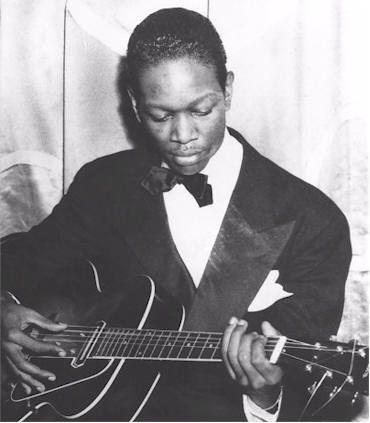

Charlie Christian (Charles Henry Christian Bonham, Texas 29 July 1916 – New York City 2 March 1942) is an American jazz and swing guitarist. Christian is often credited as an early performer of the electric guitar and a key figure in the development and evolution of cool jazz and bebop. From August 1939 to June 1941, he was a member the Benny Goodman Sextet and Orchestra. This earned him national attention. His unique single-string technique, combined with amplification, helped the guitar move out of the rhythm section to become a solo instrument. George T. Simon and John Hammond praised Christian’s improvisational skills as the greatest of the Swing Era. Gene Lees wrote in the liner notes of 1972 Columbia’s Solo Flight: The Genius Of Charlie Christian that Christian “many musicians and critics consider Christian one of the founding fathers or at least a precursor of bebop.” Christian’s influence spanned beyond jazz and swing. In 1990, Christian was inducted into The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, renamed Charlie Christian Avenue, a street in Bricktown’s entertainment district, in 2006. Oklahoma City also hosts an annual Christian-themed jazz festival. Christian was born in Bonham Texas. His family moved to Oklahoma City when he was just a child. His parents were both musicians, and he had two siblings, Edward, who was born in 1906, and Clarence (who was born in 1911). Clarence Henry Christian, their father, taught all three of his sons music. Clarence Henry, who was blinded by fever, decided to work with his sons as a busker, which the Christians called “busts,” in order for the family’s support. They would take him to the best neighborhoods, where he would be paid cash or goods. Charles began dancing when he was old enough. Charles learned to play guitar when he was 12, and inherited his father’s instruments. Zelia Breaux, an instructor at Douglass School in Oklahoma City encouraged Charles in music. Charles had hoped to play the tenor saxophone with the school band but Zelia Breaux suggested he try the trumpet instead. He was afraid that playing the trumpet would make his lips look disfigured, so he decided to quit baseball and pursue his passion for it. Clarence Christian, a Charlie Christian biographer, stated that Edward Christian was a pianist in Oklahoma City in the 1920s and 1930s. He also had a troubled relationship with James Simpson, the trumpeter. Simpson felt the need to revenge the egotistical Christian after a fight with a girl. He took Ralph Hamilton, the guitarist of Bigfoot, and began secretly teaching Charles jazz. He was taught to sing three songs solo: “Rose Room”, “Tea for Two,”and “Sweet Georgia Brown.” They took him to one of the many after-hours jam sessions along Northeast Second Street, Oklahoma City. Edward was told by them that Charles could play the one. Edward responded, “Ah, no one wants to hear their old blues.” Charles was encouraged and finally allowed to play. “What are you looking for?” He asked. Edward was shocked that Charles knew all three songs, which were popular in the 1930s. Charles played all three songs after two more encores. “Deep Deuce,” however, was in a commotion. His mother heard of it and he coolly left the jam session. Charles was soon performing in the Midwest both locally and on the roads, even as far as Minnesota and North Dakota. He was already playing electric guitar by 1936 and had quickly become a regional hit. He also jammed with some of the top performers who visited Oklahoma City such as Teddy Wilson and Art Tatum. John Hammond was told about him by Mary Lou Williams, pianist for Andy Kirk u0026 His Clouds of Joy. John Hammond, a record producer, recommended Christian to Benny Goodman. Goodman was the first white bandleader with black musicians. He hired Teddy Wilson as an arranger, Fletcher Henderson on piano and Lionel Hampton to play vibraphone in 1935. Goodman hired Christian in 1939 to join the Goodman Sextet. Many people have said that Goodman initially was not interested in hiring Christian, as electric guitar was still a new instrument. Goodman had had the opportunity to play the instrument alongside Floyd Smith and Leonard Ware, but none of them had the same ability as Charlie Christian. Goodman is reported to have unsuccessfully tried to purchase Floyd Smith’s contract from Andy Kirk. Goodman was so impressed with Christian’s playing, he hired him instead. There are many versions of the August 16th, 1939 meeting between Christian and Goodman. It suffices to say that the afternoon at the studio recording studio was not a success. Charles said in a 1940 Metronome article that “I guess neither of us liked what we played,” but Hammond tried again without consulting Goodman (Christian claims Goodman invited him to the show that night). He then placed Christian on the bandstand at the Victor Hugo restaurant, Los Angeles. The surprise was not appreciated by Goodman, who called it “Rose Room”, which Goodman assumed Christian would not be familiar with. Goodman didn’t know Charles had been raised on the tune and he brought his solo. It was the first of twenty that Goodman would hear, each one different from anything Goodman had ever heard. Christian was already in the band by the end of that version of “Rose Room”, which lasted for forty minutes. Christian’s income increased from $2.50 per night to $150 per week in just a few days. Christian was the leader in swing and jazz guitar polls by February 1940 and was elected to the Metronome All Stars. Goodman let his entire entourage go during a reorganization in the spring 1940. Goodman made sure to keep Charlie Christian. In the fall of 1940, Goodman led a Sextet that included Charlie Christian, Count Basie and longtime Duke Ellington trumpeter Cootie William. The group also featured Georgie Auld, an Artie Shaw tenor saxophonist, and Dave Tough, a band that dominated jazz polls and won another election to the Metronome All Stars. Christian’s solos are often called “horn-like”. This is because he was more influenced early acoustic guitarists such as Eddie Lang and Lonnie Johnson than by Lester Young or Herschel Evans. Christian said that he wanted his guitar sound like a tenor-saxophone. Christian was not influenced by Django Reinhardt, a Belgian gypsy-jazz guitarist. However, he was familiar with some of his recordings. Mary Osborne, a guitarist, recalled Django Reinhardt playing the solo on “St. Louis Blues” from note to note and then adding his own ideas. There were already electric guitar soloists by 1939. George Barnes, Leonard Ware and “Topsy” Eddie Durham had all recorded with Count Basie’s Kansas City Six. Floyd Smith recorded “Floyd’s Guitar Blues”, with Andy Kirk, in March 1939. Eldon Shamblin, Texas Swing pioneer, was also using an amplified electric guitar along with Bob Wills. Charles Christian, however, was the first great amplified guitarist. Mary Osborne (Nat King Cole trio), Oscar Moore, Barney Kessel and Herb Ellis were all guitarists who followed Christian, and were in some way influenced by him. Tal Farlow and Tal Ellis were also guitarists who followed Christian, as was Jim Hall a generation later. Tiny Grimes, who recorded several albums with Art Tatum can often be heard to quote Christian note-for. Christian was the first to create the modern electric guitar sound. He was followed by Les Paul, Grant Green and Kenny Burrell. King, Chuck Berry and Jimi Hendrix. Christian was also inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990 as an “Early Influence”. Christian’s exposure during his brief time with Goodman was so significant that he had a profound influence on guitarists and other musicians. On their “bop”, early recordings, “Blue’n Boogie”, and “Salt Peanuts,” you can hear the influence he had upon Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk. Miles Davis, the trumpeter, also cite Christian’s influence as an early one. Christian’s “new sound” influenced jazz in general. His dominance in jazz guitar polls lasted for two years. Be-Bop, Minton’s Playhouse Thelonious Monk and Charlie Christian, both of whom played at Minton’s Playhouse, developed a similar style to his. Charlie Christian was an important contributor in the music that would become “bop” or simply “Bebop”. Jerry Newhouse, a Goodman fan, recorded private recordings of Christian on September 19, 1939 in Minneapolis. They were taken while he was touring with Goodman, Jerry Jerome (tenor sax) and Oscar Pettiford (bass). Christian performs multiple solos, demonstrating that he was already a mature musician. Stardust, Tea For Two, and I’ve Got Rhythm are three of the Minneapolis recordings. The latter is a favourite piece for bop composers as well as jammers. Recordings of the Goodman Sextet’s March 1941 partial are more revealing of the unrestrained Christian. Christian and the rest recorded for almost 20 minutes while the engineers tested the equipment. Goodman and bassist Artie Berstein were not present. Years later, two recordings were made from the session: “Blues in B”, and “Waiting for Benny,” which showed some hints of bop jam sessions. These sessions are free-flowing and contrast with the formal swing music that Goodman recorded shortly after he arrived at the studio. The Goodman Sextet also recorded “Seven Come Eleven”, (1939), and “Air Mail Special” (1940, 1941). A series of recordings taken at Minton’s Playhouse by Columbia student Jerry Newman in 1941 using a portable disk recorder is a striking example. Newman captured Christian with Kenny Kersey and Joe Guy on trumpets and Kenny Clarke playing the piano and Kenny Clarke drumming. This was well beyond the limits of what the 78 RPM record could allow. Christian’s work on “Swing to Bop,” a later Esoteric Records company title of Eddie Durham’s “Topsy,” shows what he was capable of creating “off-the-cuff.” On “Stompin’ at the Savoy”, he uses tension and release. This technique was used by Lester Young[18], Count Basie[18], and other bop musicians. Also included in the collection are recordings taken at Clark Monroe’s Uptown House (a late-night jazz spot in Harlem, 1941) that include Oran “Hot Lips” Page. Don Byas, tenor-sax player, is also included in the recordings. The Minton recordings had been long believed to have “Dizzy Gillespie” and Thelonious Monk on them, but this has now been proved untrue. Monk was a regular at the jam sessions and Monk was a regular in Minton’s house band. Kenny Clarke stated that “Epistrophy”, and “Rhythm-a–ning” were Charlie Christian compositions that Christian performed at the Minton jam sessions. The “Rhythm-a–ning” line can also be heard on “Down on Teddy’s Hill”, behind the introduction on the Newman recordings of “Guy’s Got To Go”, but it is also a line taken from Mary Lou Williams’ song “Walkin’ u0026 Swingin'”. Clarke claimed that Christian taught him the chords of “Epistrophy” by first showing them on a ukulele. These recordings were packaged under many different titles such as “After Hours” or “The Immortal Christian”. These sessions are of poor quality, but they do show Christian working harder than on the Benny Goodman sides. Christian can be heard on the Monroe and Minton recordings taking multiple choruses from a single tune and playing long melodic lines with ease. Modern jazz is evident in his use of eighth note passages as well as triplets, arpeggio and third notes. Christian was equally adept at understatement. His Goodman sextet side “Soft Winds”, “Till Tom Special,”and “A Smo-o-o-oth One,” show that he uses very few melodic notes and is well-placed. His recordings of the ballads “Stardust”, “Poor Butterfly”, “I Surrender Dear”, and “On the Alamo” by the Sextet (1941) hint at what would later be known as “cool jazz”. Christian was credited with many of the Benny Goodman Sextet’s original tunes, although he is not credited for them all. Charlie was often seen eating poor and staying up late at jam sessions. Although he was not thought to have been a drug addict, he did reportedly use alcohol and marijuana. Christian was also hospitalized in 1940 after he contracted tuberculosis in the late 1930s. The Goodman band was then on hiatus for a brief time due to Benny’s back problems in early 1940. After the band’s short stay at Santa Catalina Island in California, Goodman was admitted to the hospital. Christian returned to Oklahoma City in July 1940, before returning to New York City on September 1940. Christian returned to his hectic lifestyle in early 1941. He went to Harlem to enjoy late-night jam sessions, after he had finished playing with the Goodman Sextet and Orchestra of New York City. He was admitted to Seaview in New York City, a sanitarium located on Staten Island. According to Down Beat magazine, he was making good progress and he and Cootie were planning on starting a band. Christian died on March 2, 1942, after a visit to the hospital that month by Marion Joseph “Taps,” Miller, a tap dancer and drummer. In 1994, a Texas State Historical Marker was placed in Gates Hill Cemetery. Christian was buried in Bonham, Texas. Charles had a daughter, Billie Jean Christian. She was born 23 December 1932 to Margretta Lorraine Downey, Oklahoma City. They did not get married. Billie Jean (Christian) Johnson died 19 July 2004. Christian was inducted into Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame in 1966, 24 years after he died. Text contributed by users is available under Creative Commons By–SA License. It may also be available under GNU FDL.