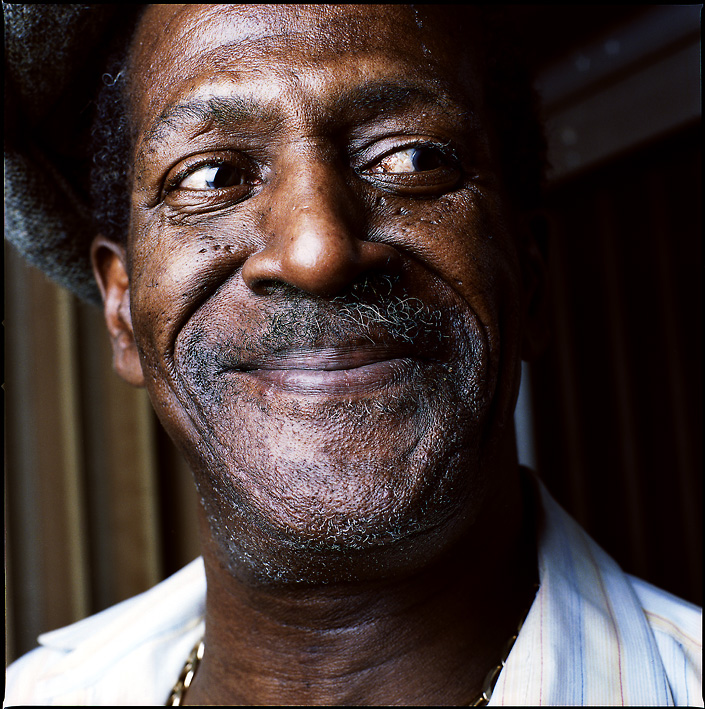

Jamaican reggae superstar and founding father of lover’s rock, whose languid vocals made him an icon of sensuality. One of Jamaica’s most beloved vocalists who was as pertinent in dancehalls as he was in bedrooms, Gregory Isaacs’ career stretched over 30 years. From the heady days of reggae through lovers rock, a genre he virtually invented, his talent reached into the modern age. Born in the Fletcher’s Land area of Kingston, Jamaica, on July 15, 1951, Isaacs arrived in the music business via the talent show circuit, a tried and true formula for many of the island’s budding singing stars. Byron Lee was the first in the industry to spot his talent and brought him and Winston Sinclair into the studio to record the duet “Another Heartbreak” in 1968. Sadly, it went nowhere, and Isaacs decided to try his fortunes with a new vocal trio, the Concords. They set up home at Rupie Edwards’ Success label, and over the next couple of years released a number of singles, including one with Prince Buster, but none caught the attention of the Jamaican public. In 1970, the Concords folded and Isaacs struggled on alone. His initial self-productions were similarly unsuccessful, while further cuts with Edwards did no better. Regardless of this poor track record, in 1973 Isaacs set up his own record store and label, African Museum, in partnership with Errol Dunkley, a young singer with a string of hits to his own name. Apparently some of Dunkley’s own magic wore off and one of the label’s first releases, Isaacs’ own self-produced “My Only Lover,” was an immediate hit and the floodgates opened wide. Besides African Museum’s offerings, Isaacs helped keep the label solvent by recording with virtually every producer on the island for a stream of hits that showed no sign of abating. Between 1973 and 1976 alone, the singer released more material than most artists do in a lifetime, virtually all of it timeless classics. Isaacs’ early albums inevitably gathered up strings of these hits, while usually also including a few new songs. Released in 1975, In Person, for example, features a heavy-hitting collection of successes for producer Alvin Ranglin and was followed up in 1977 by Best Of, Vol. 1 and Best Of, Vol. 2 in 1981. (The Heartbeat label would bundle up this material across three CDs for the U.S. market: My Number One, Love Is Overdue, and The Best Of, Vols. 1-2). Similarly, 1976’s All I Have Is Love includes a hit-filled package of Sydney Crooks productions. Extra Classic, co-produced by Isaacs, Pete Weston, and Lee Perry, is also stuffed with chartbusters and showcases the singer’s deepest roots material. The latter album appeared on African Museum, cut with a diverse range of producers, across three volumes titled Over the Years. In 1977, the U.K. was treated to an equally dread experience via Mr. Isaacs, released on Dennis Brown’s DEB label. (Turnabout is fair play and Brown had released several classic albums of his own on African Museum.) By this time, the two polar sides of Isaacs were apparent: the roots singer, whose emotive sufferer’s songs and cultural numbers were filled with fire, and the crooning lover, whose passionate declarations of devotion quivered with emotion. Eventually, the vocalist’s ties to the lovers rock scene saw his reputation as the Cool Ruler overshadow the equally impassioned roots performer, but his work in the latter half of the ’70s shows his heart was true to both. Isaacs was quick to take advantage of the rise of the DJs; producer Ranglin paired him with a string of cutting-edge toasters for another flood of hits, beginning in 1978. It was at this time that he first hooked up with DJ Trinity, a partnership maintained into the next decade across a stream of seminal singles. By now, Isaacs was too big a talent to ignore, and in 1978 he signed with Virgin’s Frontline label. That same year, the singer had a featured role in the classic Rockers movie. Inexplicably, however, as Isaacs was poised on the brink of international success, he failed to set the rest of the world alight. His debut Frontline album, the excellent Cool Ruler, barely ruffled a feather outside Jamaica. It did, however, provide most of the material for Slum: Gregory Isaacs in Dub, which boasted fat rhythms by the Revolutionaries, keyboardist Ansel Collins with Prince Jammy, and Isaacs himself behind the mixing board. Cool Ruler’s follow-up, 1979’s Soon Forward, was filled with hits that would soon become classics, but also did not make the slightest dent on the world beyond Jamaica. The latter’s title track was produced by Sly & Robbie and gave the pair’s new Taxi label its first hit. Isaacs cut several more great singles with the team, which were brought together for 1980’s Showcase album. Even with Frontline out of the picture, Isaacs continued going from strength to strength. Inking a U.K. deal with the Pre label and with his fortunes secure in Jamaica, the artist continued turning out hit after hit. His Pre debut, The Lonely Lover, and its follow-up, 1981’s More Gregory, both boast the Roots Radics and a host of Jamaican hits that range from lovers rock to deep roots and on to the emerging dancehall sound. No wonder the singer was a hands-down success at the first Reggae Sunsplash. It was at this point that Island stepped up to the plate and signed the singer to their Mango imprint. Virgin label head Richard Branson must have cursed his own stupidity, as Isaacs immediately repaid his new label’s faith with his biggest hit of all, “Night Nurse.” The song titled his Mango debut, another masterpiece, and again featured the steaming Roots Radics. Amazingly, as the song spread around the world, the singer sat whiling his time away in a Jamaican jail as the result of a drug arrest. He was released later in 1982 and immediately entered the studio to record Out Deh with producers Errol Brown and Flabba Holt. Once again able to take the stage, Isaacs played a series of awe-inspiring shows over the next year, captured on both 1983’s Live at Reggae Sunsplash and the following year’s Live at the Academy Brixton albums. Behind the scenes, Isaacs joined the shadowy conspiracy of vocalists determined to return vocalists to their rightful place in the market by flooding the shops with music. An all-star cast of veteran singers joined the plot, including Dennis Brown, John Holt, Delroy Wilson, and many more, but none would reach the prolificacy of the determined Isaacs. It’s been estimated that the singer released up to 500 albums (including compilations) in Jamaica, the U.K., and the U.S. combined. The singer recorded with anyone and everyone and was just as quick to revise his old songs as create fresh ones. Although none of these are entirely disposable, inevitably the quality of Isaacs full-length work began to decline in the mid-’80s. The Ted Dawson-produced Easy and All I Have Is Love, Love, Love, for example, certainly have their charms, but are hardly crucial. But that didn’t mean the hits had dried up. Those 500 records are albums only, not singles, and the shops (and charts) continued to overflow with Isaacs’ 45s. And the rise of ragga just added hot new producers to the singer’s packed recording diary. In 1984, producer Prince Jammy, equally intrigued with the changing sounds of dancehall, brought Isaacs into the studio for the superb Let’s Go Dancing, while also pairing the singer with Dennis Brown for Two Bad Superstars Meet. The latter proved so popular that a second set, Judge Not, appeared the next year. The two singers dueted again on a track on Isaacs’ 1995 solo album, Private Beach Party, which also boasted an exquisite “Feeling Irie,” which paired him with Carlene Davis. The album was produced by Gussie Clarke, a man with the determined goal of creating an international crossover sound via his own one-stop operation à la Motown. He hadn’t quite succeeded yet, but Private Beach Party helped lay the groundwork. In 1987 Isaacs collaborated with the equally sweet-singing DJ Sugar Minott for the Double Dose album. Isaacs swiftly found himself a dancehall hero. It was during this period that Isaacs also recorded an album for King Tubby. Warning boasts the magnificent rhythms of the Firehouse Crew, and a dark atmosphere of foreboding slinks through the entire set. It was not released at the time and only came to light after the great man’s murder in 1989. By then, Isaacs had already stormed the world, digital or otherwise, with the 1988 Gussie Clarke-produced “Rumours” (whose rhythm would launch scores of further version hits, including J.C. Lodge’s “Telephone Love,” an even bigger smash). The masterful Red Rose for Gregory boasts a clutch of hits beside equally sublime non-45 tracks, all cut for Clarke. The pair’s follow-up, 1989’s I.O.U., is arguably an even stronger album. That same year, Clarke reunited Isaacs and Brown for the No Contest album. Isaacs continued to cut seminal singles with Clarke, while also recording with a host of other producers. In 1990, the singer joined forces with Niney Holness for the excellent On the Dance Floor album. The next year saw Fatis at the controls for Call Me Collect, which boasts Sly & Robbie and Clevie, while Bobby Digital adds his unique production sound to 1991’s Set Me Free. And having inked a deal with RAS in the U.S., that label’s head, Doctor Dread, oversaw 1992’s memorable Pardon Me. Philip Burrell was in the producer’s chair for 1994’s Midnight Confidential album. But there was a slew of lesser titles as well; while Isaacs seemed able to always hit the mark with singles, albums required more effort than he was often willing, or able, to give. No Intention and Boom Shot, both from 1991, are workaday records, with the singer on autopilot. Past & Future sounds promising and features such illustrious guests as Sly & Robbie, J.C. Lodge, Winston Riley, and Boris Gardiner on material both new and old, but it’s obvious that no one’s heart is really in it, Isaacs’ least of all. The patchy Rudie Boo (released by Heartbeat in the U.S. as My Poor Heart) suffers from a similar lack of interest on the singer’s part. At least 1993’s Unlocked featured a stronger set of songs, but much of Isaacs’ releases throughout the ’90s were hit-and-miss affairs. Midnight Confidential, for example, is totally disposable, except for the magnificent “Not Because I Smile.” Most of the albums frequently revisit older hits, which even at their worst tend to stand out from the newer fare. Younger or less experienced producers were in particular danger, and as the years progressed it was only the toughest and most innovative producers who could coax the best from the singer. Alvin Ranglin, for example, wrung an exquisite set of emotionally riven songs from Isaacs for 1995’s Dreaming. Mafia & Fluxy’s fat, dubby rhythms inspired one of the singer’s best performances in ages for Hold Tight two years later. The wisest course in negotiating one’s way through the minefield of latter-day Isaacs is to look at the production credits. If you like the slick production that’s the trademark of Bunny Gemini, chances are you’ll appreciate 1996’s Mr. Cool. Junior Reid likes diversity, and thus, Not a One Man Thing has that in spades, from the slacker-themed “Big Up Chest” to a remodeled “Don’t Dis the Dance Hall.” Steely & Clevie laid down the rhythms for 1998’s Hard Core Hits; if you’re not a fan of their digitized dancehall mayhem, choose another album. King Jammy is let loose on 1999’s Turn Down the Lights, and while not up to the standards of Let’s Go Dancing, it’s still an enjoyable ride. Joe Gibbs, Errol Thompson, and Sydney Crooks lent their expertise to So Much Love, another one of Isaacs better later offerings. The singer began the new millennium with aplomb on Father and Son, which, true to the title, features Isaacs and his son Kevin. The duets are gorgeous, while the younger Isaacs is given plenty of room to prove that his talent is equal to his dad’s. The next year, I Found Love marked the second time the two worked together. In between times, the singer continued to impress audiences live, and his recorded output continued sporadically during the remainder of the decade. However, by 2007 he had reportedly lost his teeth due to crack cocaine addiction, and he was later diagnosed with lung cancer, which spread and ultimately took his life. Gregory Isaacs died at his home in London on October 25, 2010 at the age of 59. from allmusic