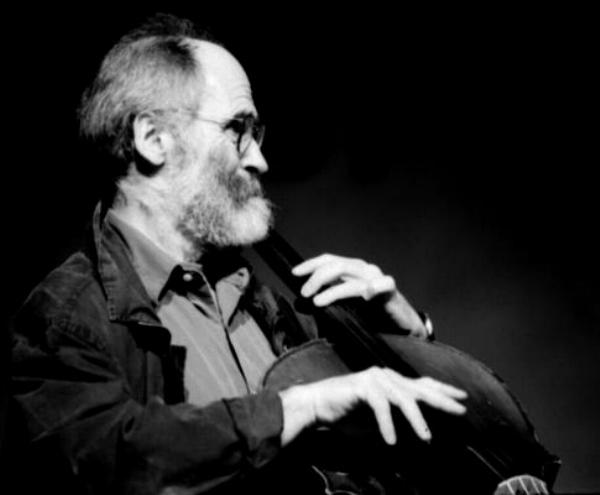

Polish-born avant-garde trombone master got interested in improvising with jazz music from the opposite end of the spectrum, early Dixieland style. As a child, he was afflicted by polio and would have to stop touring in his later years. As a child, his first musical inspirations were the New Orleans jazz sounds created by George Lewis and Kid Ory. Ironically, both of these jazz legends have a connection to the German musician. He was drawn into the world of joyous extrapolation by the New Orleans players, who drew him in with their swaggering tones and fat hearts. George Lewis, a Chicago trombonist who belonged to the Assocation for the Advancement of Creative Musicians was the younger of the many young improvising trombonists who were inspired by Gunter Christmann’s fluid use of new musical language on this heavy and complicated instrument. Christmann tried his hand at the banjo, a New Orleans instrument that was very popular, before finally settling on the bone challenge. After hearing recordings of Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane, Christmann became interested in free jazz. He began playing in European groups, which created their own versions of the noisy, freewheeling music. This music was often criticized for being angry and full of hatred. To be able to perform in this type of music with others, the instrumental effects that a trombonist must master were strikingly similar in style to the New Orleans trombonists’ love of slurry slides and overblowing. Christmann used a variety of plungers and mutes to achieve different tones. Rudiger Carl, a Frankfurt clarinetist and tenor saxophonist was his partner. Between 1972 and 1974, Christmann was also a member of several quintets led by Peter Kowald. It was tiring times as the bandleader was known for driving home immediately after the last gig, regardless of how far away or late it may have been. This desperate act of desperation, known as “pulling in a Kowaldski”, is a bleary-eyed act. These were also the first improvising experiences for Paul Lovens (Aachen drummer), who played in these groups from 1972 to 1981. He has continued his improvising skills over the years, playing with Christmann in various settings, from duo to full-sized orchestras. Christmann formed a regular duo with Detlef Schonenberg from 1972 to 1981. They worked together with dancers and made many recordings that were influential among other improvisers such as FMP’s We Play. In a music that was partially related, the trombone seemed to be an ideal expressive instrument. Harald Boje, a synthesizer player, was his first contact with electronic music. He joined the large Globe Unity Orchestra under the loose direction of pianist Alexander Schlippenbach. This project has included many European and American musicians over the years, not just George Lewis. The large group recorded some compositions Christmann composed for them, but not to a great extent. He began performing solo in 1975, when there were many other horn players doing the same thing. Infuriatingly, travel agents booked whole bands to accommodate this idea. Christmann was a great player in a challenging idiom. He used space and silence to his advantage, but he could also unleash enough thunderous trombonics to drown an entire elephant. Many trombonists copied his technique, including the use of the plunger and various mutes. He recorded and performed in a duo with Tristan Honsinger, an American expatriate cellist. This resulted in some of his finest work. The well-planned combination of players took Christmann over the edge. His florid, almost hysterical style took him to the next level. He began to follow the trend of loose conglomerations, which could fill a concert with improvisations in many combinations. Vario was his version, and it was recorded by Moers Music. Lovens, Maggie Nichols (British vocalist) and John Russell were part of this group. Christmann created a 1982 presentation called Deja Vu, in which he combined film production, electronic music and lighting effects with contributions from Torsten Muller, bassist. Critics encouraged Christmann to go back to his trombone and it was not well received. He has had to concentrate more on special projects since the late 1990s, and has greatly restricted his touring. Allmusic