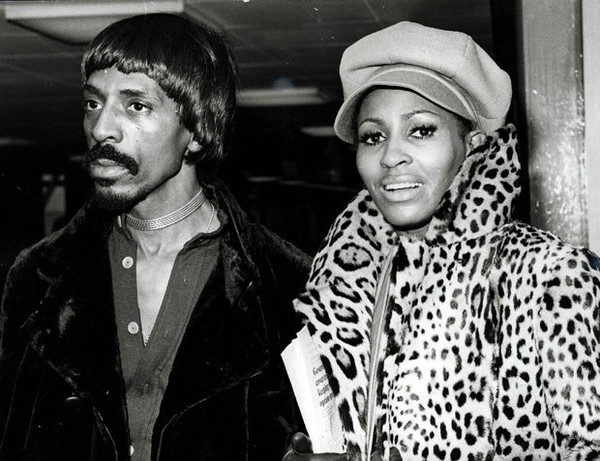

As husband and wife, Ike & Tina Turner headed up one of the most potent live acts on the R&B circuit during the ’60s and early ’70s. Guitarist and bandleader Ike kept his ensemble tight and well-drilled while throwing in his own distinctively twangy plucking; lead vocalist Tina was a ferocious whirlwind of power and energy, a raw sexual dynamo who was impossible to contain when she hit the stage, leading some critics to call her the first female singer to embody the true spirit of rock & roll. In their prime, the Ike & Tina Turner Revue specialized in a hard-driving, funked-up hybrid of soul and rock that, in its best moments, rose to a visceral frenzy that few R&B acts of any era could hope to match. Effusively praised by white rock luminaries like the Rolling Stones and Janis Joplin, Tina was unquestionably the star of the show, with a hugely powerful, raspy voice that ranks among the all-time soul greats. For all their concert presence, the Turners sometimes had problems translating their strong points to record; they cut singles for an endless succession of large and small independent labels throughout their career, and suffered from a shortage of the strong original material that artists with more stable homes (Motown, Atlantic, Stax, etc.) often enjoyed. The couple’s well-documented marital difficulties (a mild way of describing Ike’s violent, drug-fueled cruelty) eventually dissolved their partnership in the mid-’70s. Tina, of course, went on to become an icon and a symbol of survival after the resurgence of her solo career in the ’80s, but it was the years she spent with Ike that made the purely musical part of her legend. Izear Luster “Ike” Turner, Jr. was born in Clarksdale, MS, in 1931; initially a pianist, he formed his first band in high school and put together the Kings of Rhythm in the late ’40s. In 1951, that group cut the pivotal “Rocket 88,” a tune often pinpointed as the first ever rock & roll record; however, since sax player Jackie Brenston took the vocal, the song was credited to Brenston & His Delta Cats rather than Turner & the Kings of Rhythm. Not long after, Turner switched from piano to guitar, and he and his band became a prolific session outfit in Memphis, backing various Sun artists and bluesmen during the early ’50s. Turner moved the Kings of Rhythm to East St. Louis in the mid-’50s, where they became kingpins of the local R&B circuit. In 1956, he met a teenage, gospel-trained singer from Nutbush, TN, named Anna Mae Bullock, and promised her a chance to sing with his band. That chance kept failing to materialize, until one night Bullock simply grabbed the microphone and started belting. Impressed, Turner made her a part of his revue, changing her name to Tina. After Tina became pregnant by the band’s saxophonist, Raymond Hill, she moved into Turner’s house, an arrangement that led to their own relationship; the two were married in 1958 and soon had a child of their own. In late 1959, Turner’s band entered the studio to cut a song called “A Fool in Love” for the Sue Records label. The scheduled male vocalist failed to show up for the session, and Tina was pressed into service. Released in 1960, “A Fool in Love” shot to the number two spot on the R&B charts, also making the pop Top 30. Tina was now clearly the focal point of the act, which Turner rechristened the Ike & Tina Turner Revue; with a large, horn-filled ensemble and a group of leggy backup singers dubbed the Ikettes (who complemented Tina’s short-skirted, uninhibited gyrating), the Revue eventually developed a reputation for putting on one of the most exciting live shows in R&B. The R&B-chart hits came fast and furious during the early ’60s: 1961’s “I Idolize You” (number five) and “It’s Gonna Work Out Fine” (number two), 1962’s “Poor Fool” (number four) and “Tra La La La La” (number nine). It was an impressive run, but the well went dry over the next several years; Ike supplied much of the band’s original material, and although he was responsible for many of the early successes, he simply wasn’t a world-class songwriter who could deliver hit-caliber tunes with regularity. Much of the Revue’s repertoire consisted of bluesy, chitlin circuit R&B that wasn’t exceptionally memorable. Ike & Tina branched out from Sue Records and spent the next few years issuing records on additional labels, including Kent, Modern, and Loma. While they had some undeniable high points and several chart entries, none reached the level of their initial run of Top Ten hits. In 1966, the Turners worked with legendary producer Phil Spector, who was seeking a way to restore his artistic and commercial standing at the forefront of pop music in the wake of advances by the Beach Boys and Beatles. The powerful instrument that was Tina’s voice appealed to Spector’s sense of grandeur, and he conceived of a massive-scale production framing that voice that would rank as his greatest masterpiece. Ike already had a reputation for demanding control, and Spector struck his deal accordingly: although the records would be fully credited to Ike & Tina Turner, Ike would not be allowed to enter the studio or alter the finished recordings (in effect, Spector was paying him not to meddle). The centerpiece of Spector’s collaboration with Tina was “River Deep – Mountain High,” a monumental pop symphony that cost over $22,000 to produce (in 1966, this was a whopping sum for an album, let alone a single). The single represented Spector’s so-called Wall of Sound style at its most gloriously excessive, and Tina’s was one of the few voices in popular music strong enough to cut through the monolithic orchestral backing. With the high cost and his own slipping stature, Spector was betting the farm on “River Deep – Mountain High,” and although it rocketed into the British Top Five and made Tina a star in the U.K., it flopped in America, where its mixture of black and white musical aesthetics was still slightly ahead of its time. A crushed Spector retreated from the music business not long after, and his Philles label yanked the accompanying album of the same name from American release (Spector wound up producing only five of the 12 cuts). Although some critics dismiss “River Deep – Mountain High” as overproduced bombast, many still consider it one of rock’s greatest singles; George Harrison famously described it as “a perfect record from start to finish.” After the Spector deal fell through, Ike & Tina returned to their somewhat mercenary recording habits, cutting songs for Modern and Innis, then moving to Minit and Blue Thumb in 1969. That year, they went on the road as the opening act for the Rolling Stones, and Ike slightly retooled the Revue’s sound to appeal to white rock audiences in addition to their core black following. In 1970, they signed with Liberty/United Artists and recorded Come Together, which incorporated contemporary rock & roll covers into their repertoire; versions of the Beatles’ title track and Sly & the Family Stone’s “I Want to Take You Higher” made the R&B Top 30. Released later that year, Workin’ Together became the most popular album of their career, making the Top 25 on the strength of a storming reinterpretation of CCR’s “Proud Mary.” Featuring a notorious spoken intro by Tina, the “nice…and rough” version of “Proud Mary” gave Ike & Tina their first Top Five hit on the pop charts, and returned them to the same heights on the R&B side as well; it also won them a Grammy. The covers gimmick couldn’t last forever, though, and their formula soon grew predictable; their last major success was 1973’s “Nutbush City Limits,” a semi-autobiographical song written by Tina that made the R&B Top 20 and just missed that placing on the pop side. By that point, Tina had grown increasingly uninterested in the duo’s well-established act, and was tiring of the largely unchallenging material she continued to perform. Unfortunately, the music itself wasn’t the only factor in Ike & Tina’s downturn. As a bandleader, Ike had long been a disciplinarian, but during the ’60s he developed severe addictions to alcohol and, especially, cocaine. Wanting to maintain control over the star of his show at any cost, Turner kept his wife in line through an increasingly violent pattern of emotional and physical abuse; often drug-related, his flights of rage could result in severe beatings or burns that pushed Tina to attempt suicide in 1968, according to her autobiography. She continued to endure Ike’s dominance through the early ’70s, and her performances were clearly weary by the end; finally, she walked out on her husband and generally declined to pursue claims for financial compensation from their work together. Their divorce became official in 1976. After a long period of struggle, Tina re-emerged triumphantly in the ’80s as a superstar solo act; Ike, meanwhile, ran his own recording studio for a time, but his drug problems worsened, resulting in several arrests. Sadly, and perhaps fittingly, he was serving prison time when he and his former wife were jointly inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1991, and was unable to attend the ceremony. from allmusic