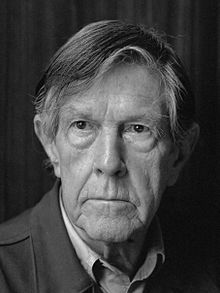

Editor’s Note: John Cage might seem oddly placed on a jazz website. Even one with a large section on jazz, John Cage’s influence on avant-garde music cannot be overlooked. His ‘prepared piano” innovation has also found a permanent place in the world modern jazz piano. Along with several other composers, he also helped to introduce the concept of improvisation into the Western concert hall music. Cage’s fascination with African, Asian, and other non-Western musical styles has had a lasting impact on modern music. John Cage, Jr., American avant-garde composer, was born September 5, 1912 in Los Angeles, California. He died August 12, 1992 in New York. His innovative compositions and unconventional ideas greatly influenced music of the mid-20th century. Cage, the son of an inventor and Pomona College graduate, briefly traveled to Europe before returning to the United States. Cage returned to the United States in 1931 and studied music with Adolph Weiss (Richard Buhlig), Arnold Schoenberg, Henry Cowell, and Adolph Weiss. Cage founded a percussion group to perform his compositions while he was a teacher in Seattle (1938-40). Cage also tried out works for dance. His subsequent collaborations with choreographer and dancer Merce Curnningham sparked a long and creative partnership. Cage’s first compositions were written using the 12-tone method taught by Schoenberg. However, by 1939, he was experimenting with more unconventional instruments like the “prepared piano”, a modified piano that has objects placed between the strings to create percussive or otherworldly sound effects. Cage experimented with radios, tape recorders and record players in an effort to move beyond the boundaries of Western music and its ideas of meaningful sound. Cage’s 1943 concert with his percussion group at the Museum of Modern Art, New York City marked his first steps in becoming a leader of America’s musical avant-garde. Cage began to study Zen Buddhism and other Eastern philosophies over the years and realized that music is a natural process that involves many activities. Cage began to see all sounds as musical and encouraged people to pay attention to all sonic phenomena rather than just those selected by composers. He cultivated the principle indeterminism of his music to achieve this goal. To ensure randomness and eliminate personal taste, he used many devices: unspecified performers and instruments, complete freedom, exact notation, freedom of sound duration and whole pieces, inexact note, and sequences of events determined randomly through consultation with the Chinese Yijing (I Ching). These freedoms were extended to other media in his later works. For example, a 1969 performance of HPSCHD might include light shows, slide projections, costumed performers as well as the 7 harpsichord soloists (I Ching) and 51 tape machines. Cage’s most well-known pieces include 4’33′(Four Minutes and Thirty-3 Seconds, 1952), which is a piece where the performers are utterly silent for a certain amount of time. (The amount of time is up to the performer). 4 (1951), for 12 randomly tuned stations, 24 performers and conductor; the Sonatas and Interludes (46-48), for prepared piano; Fontana Mix (58), which is a piece that uses a series programmed transparent cards to create a graph for random selections of electronic sounds; Cheap imitation (1969), an “impression”, of Erik Satie’s music; and Roaratorio (1979), which is an electronic composition that utilizes thousands of words from James Joyce’s novel Finnegans Wake. Cage wrote several books including Silence: Lectures, Writings (1961), and M: Writings ’67 – ’72 (1973). Cage’s influence reached well-known composers such as Morton Feldman and Morten Hiller, Christian Wolff, and Earle Brown. His work was also recognized for its contribution to the development of traditions that range from minimalist and electronic music, to performance art. From www.britannica.com