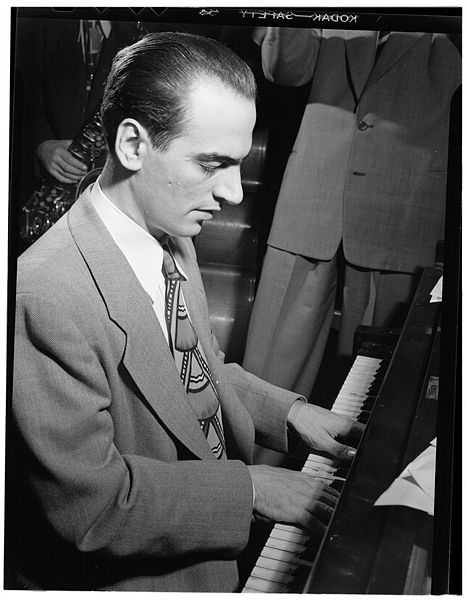

(19 March 19th, 1919, Chicago) Pianist. He died 18 November 1978. He was born during an epidemic and became blind at the age of eleven. He was also a reed player and played in rhumba and dixieland bands. Recorded in NYC ’45, with trombonist Earl Swope, (b. 4 Aug. 22 in Hagerstown MD; died 3 Jan. 1968, Washington DC), the “Lost Session” sextet. Tristano’s speed on solos on two takes to ‘Tea For Two is remarkable, given his later reputation as being too cerebral. His love for counterpoint and use of block chords made him an exceptional artist despite his work not being commercially successful. Art Tatum and Duke Ellington were his harmonists. His music was rich and complex, but he and his students could create endlessly beautiful variations from a few old pop songs. This is similar to how Bix Beiderbecke created magic with early jazz tunes. Tristano, a rhythmic genius, was also his man. His unique way of putting it all together was unmatched. He wanted hornmen not to be inflected, so the result would depend more on musical construction than emotion. Some thought his music was cold, but Terry Martin said that ice can burn. He wanted the rhythm sections to play a simple beat in order for his invention to have its desired effect. This resulted in his own metre of angularity, subtle pulse variation and swinging. His students would learn old solos that were originally played on other instruments to help them develop a sense for solo construction. He was not too cerebral. He said that he could not play and think simultaneously (‘It is emotionally impossible,’ Ira Gitler). He also made a distinction between emotion and feeling. In the 1960s, he believed that jazz was what you can do before you get screwed-up. The other is what happens after that happens. While musicians were fascinated by his performance, the public was confused because it was freed from reassuring cliches. Jazz is supposed to express the moment. However, the best music in any genre requires an artistic sensibility. Tristano’s music was instantly recognisable. Tristano was always considered avant-garde and did not believe that jazz had made any progress. Ted Brown, Lee Konitz, and Warne Marsh were his students, as well as guitarist Billy Bauer, who was a member of the Woody Herman group. Clyde Lombardi recorded a Lennie Tristano Trio with Bauer for Keynote ’46. ’47 with Bob Leininger: 19 tracks contained eleven alternate takes (six versions of ‘Interlude’ aka ‘Night In Tunisia’). Plus an untitled fast-blues nearly four minutes in length, were compiled on a Mercury disc. Capitol ’49 recorded the Lennie Tristano Sextet with Konitz Marsh, Bauer and Arnold Fishkin as bass players. Denzil Best was on drums at another session, while Harold Granowsky played one track. Seven tracks were included. “Intuition” and “Digression”, in which the players were instructed to play without any key, chord structure, melody, or melody. This was many years before “free jazz” became a popular term. Capitol was furious and refused to pay for the session. It was issued as Capitol CD Intuition 1996, which included a Warne Mars album and notes by Martin. Tristano was an artist who was constantly evolving and had great originality. He was also aware that he could not consolidate his position. This was why he said of the ’49 sextet: ‘Instead consolidated our position, it was always being developed, and that’s not a way to sell anything.’ Prestige recorded a similar lineup without Bauer as the Lee Konitz Quartet ’49. Although some sources claim Tristano played piano in this recording, discographies indicate that it was Sal Mosca, a colyte (b 27 April 1927, Mt Vernon NY). Three takes of Tristano’s ‘Victory Ball’ were recorded by the Metronome All-Stars date ’49. They were based on Gershwin’s ‘S Wonderful’ and were very warm. Charlie Parker not only improvised the chords, but also (unusually for him), on Tristano’s theme. Although Tristano was often critical of other musicians’ music, he loved Parker. He opened a NYC studio in ’50 and focused on teaching, knowing he wasn’t going to make any money as a leader. Later students included Ronnie Ball, an English-born pianist, and Peter Ind, a bassist. Ind recorded with Tristano on The Real Lee Konitz (’57-75 on Atlantic); he also recorded ’57-75 on his Wave label. In the ’80s, he ran a London club called the Bass Clef. Bob Wilber, Bud Freeman and other musicians came to see Tristano. Freeman, the great Chicago-style/Swing Era Tenor Saxist, stated that Tristano helped him gain confidence when he was at a low point. Tristano recorded two tracks with Ind Haynes and Roy Haynes for his Jazz label ’51. Some of the overdubbing was done in mastering, but nobody noticed. He was a great keyboard player, but he couldn’t speak without playing duets. The classic jazz album ‘Descent into the Maelstrom’ (originally on East Wing, then Inner City records) deserves to be reissued on CD. Konitz recorded Atlantic ’55 with a four-piece band that included Gene Ramey on bass and Art Taylor on drums. Solo ’62 tracks were compiled under Lennie Tristano/The New Lennie Tristano. He was amused when people listened to tapes rather than the music. Although the music is not considered swinging, it was extremely rhythmic. Max Harrison said that even if one note were used, they would still be more rhythmic than jazz with better resources. His Jazz Records is now a division in the Lennie Tristano Jazz Foundation. CDs include Live At Birdland 1949 with Jeff Morton on drums; Wow (live in NYC c. 1950 with Marsh, Konitz and Ind on drums); Live In Toronto 1952 with Marsh and Henry Grimes on bass and Nick Stabulas drums; Continuity (in Marsh’s studio ’64-5), Note To Note with Dallas (drums overdubbed at Lennie’s request by Carol Tristano on the drums were played by Tony Weyburn) and Manhattan Studio (’55-6 These are duplicates of LP issues that average 44 minutes. But Tristano’s recordings sound like Parker’s. Every scrap is valuable. In 1998, there was another: a 39-minute Concert In Copenhagen that Danish Radio recorded in ’65. The Lennie Tristano Memorial Concert featured Marsh, Mosca and Max Roach as well as Eddie Gomez, Sheila Jordan and many other musicians. Sonny Dallas, a bassist, died 22 July 2007. He was 76 years old. He had been a professional in Philadelphia in the 1940s and went to New York in 1955. There he recorded with Phil Woods, Warne Marshall, and Lee Konitz. He began a teaching career in Suffolk County in the late 1960s. from http://www.donaldclarkemusicbox.com