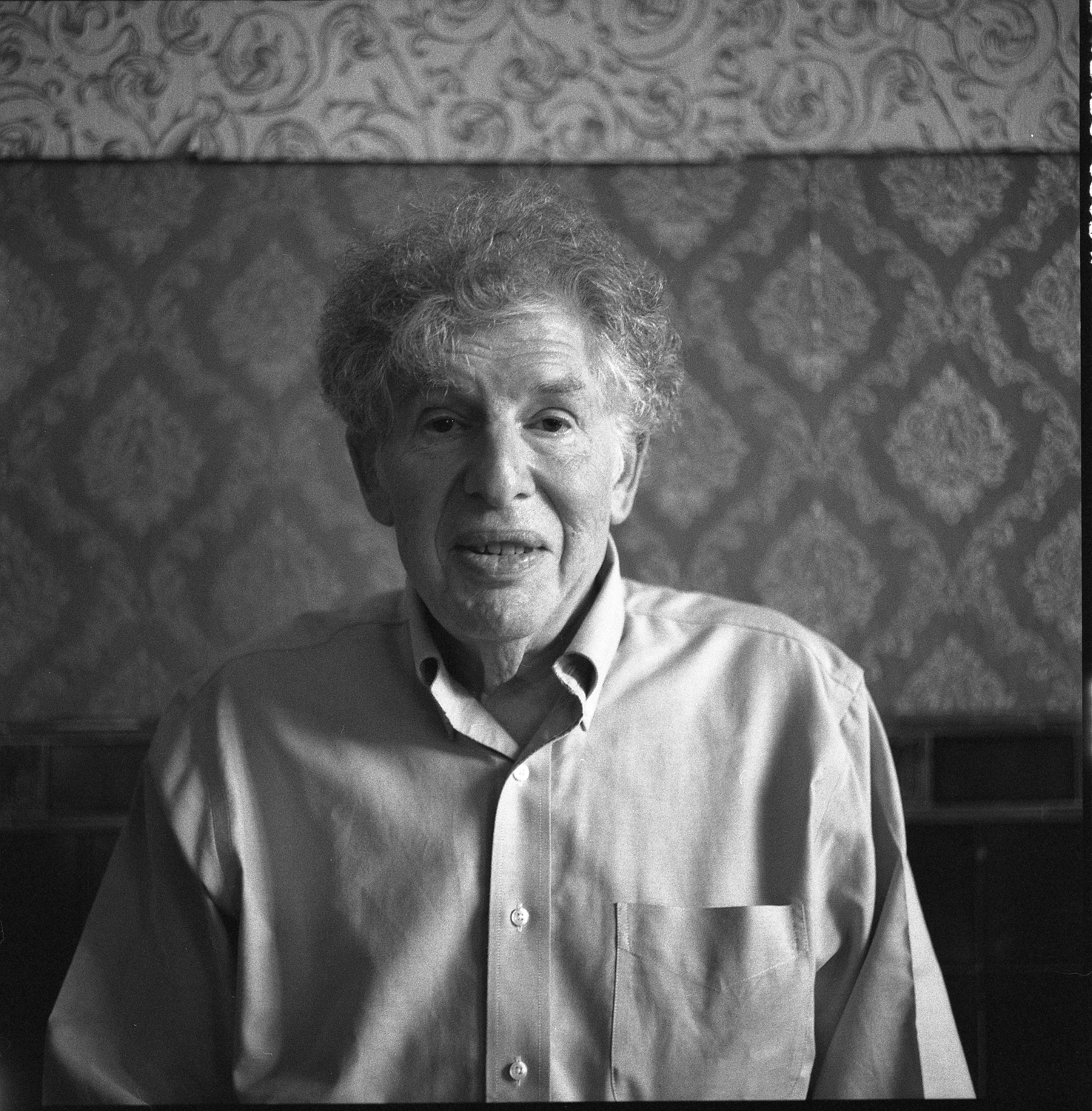

Richard Lowe Teitelbaum, May 19, 1939 – April 9, 2019, was an American composer and keyboardist. He was a student of Allen Forte and Mel Powell and was well-known for his live electronic music performances and synthesizer performances. He was a pioneer in brain-wave music. Richard Lowe Teitelbaum, the son of Sylvia Lowe and David Teitelbaum, was born in New York City on May 19, 1939. From the age of 6, he took piano lessons and was exposed to jazz music. In an interview with Kurt Gottschalk, Teitelbaum recalls being in Times Square’s balcony for a Louis Armstrong concert. Teitelbaum was a pioneer of electronic music. He created “brainwave music” in the early 1960s after urging Robert Moog, inventor of the modular synthesizer, to allow neural oscillations to be used as control voltages. Teitelbaum was the first to bring a Moog synthesizer into Europe. He incorporated it into performances in Musica Elettronica Viva with his partners Alvin Curran, a composer, and Frederic Rzewski, a pianist. Sometimes, the ensemble used biofeedback from audience members to create music. This included brainwaves as well as electrocardiograms and other signals. The process was used in “Organ Music,” a 1968 composition with Steve Lacy, soprano saxophonist, and Irene Aebi, vocalist. Musica Elettronica Viva used Teitelbaum’s biofeedback techniques in a piece called “SpaceCraft.” Teitelbaum was also a pioneer in musical globalism. In 1970, while studying ethnomusicology, Teitelbaum formed the World Band. This group of master musicians from North America, India, and the Middle East improvised together. Separately, Teitelbaum studied the shakuhachi, which is a Japanese bamboo flute. In 2002, “Blends”, a shakuhachi piece that he wrote in 1977, was finally released on an album with that title. It was included on The Wire’s top classical albums of 2002 list. His work also included computer-assisted keyboards and interactive software. He was featured on Piano Plus (2013), which featured Rzewski and Ursula Oppens as well as Takahashi. Teitelbaum was a big fan of improvisation, but he explained that he had been working with computer-assisted pianos and interactive software for many years. He wrote, “For many decades, my approach to musical improvisation has concerned developing and realizing one’s musical potential,” in a paper for Contemporary Music Review. He was able to connect with many of the most prominent composer-improvisers in the post-1960s avantgarde. He told me that he was not a jazz musician and had no pretensions. “But I have played with many jazz musicians, though some don’t like being called that like Roscoe Mitchell, Anthony Braxton, or George Lewis. He named three prominent members of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. They share a commitment to original music that is unaffected by conventions and above all classification. Braxton was Teitelbaum’s closest friend, and he produced a number albums together, including Time Zones in 1977. His other improvising collaborators were pianist Marilyn Crispell, Joelle Leandre, and violinist Leroy Jenkins. Crispell tells NPR Music that Crispell was sensitive to electronics, especially in the early days when people were blasting music as loudly as possible. His most recent recording credit is her 2018 album Dream Libretto with Tanya Kalmanovitch playing violin and Teitelbaum as electronics. Teitelbaum had a long relationship with Andrew Cyrille (master drummer), with whom he recorded Double Clutch in 1981. The Declaration of Musical Independence, Cyrille’s 2016 album, features Bill Frisell as guitarist and Ben Street as bassist. Teitelbaum plays the synthesizer and acoustic piano. Although he sounds completely like himself, the results include Teitelbaum’s “Herky Jerky” and guitarist Bill Frisell on The Declaration of Musical Independence 2016. Teitelbaum was already fascinated by John Cage, avant-garde composer/conceptualist, when he enrolled at Haverford College as a music major. He studied composition with Mel Powell and music theory at Allen Forte. Henry Cowell, a great composer and music theorist, was also a friend. This sparked his interest for traditional Japanese music. Teitelbaum would become the executor of Cowell’s estate. 1964 was the year that Teitelbaum received a Fulbright Fellowship. He studied with Goffredo Petraassi in Italy. The following year, he returned to study under another famous composer, Luigi Nono. In 1976, Teitelbaum was granted another Fulbright to go to Japan to study gagaku (or imperial court music) and shakuhachi. Teitelbaum received a masters degree in music from Yale. In 1988, he joined Bard College’s faculty, where he was the Director of the Electronic Music Studio. In 2002, he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in Music Composition. He used it to create Z’vi (the second in a trilogy of operas that were inspired by Jewish mysticism). He also composed “Concertino for Orchestra and Piano,” a classical work that he wrote for Sakurazawa’s Woodstock Chamber Orchestra. Teitelbaum and Alvin Curran joined Teitelbaum in a concert tour in 2017 to mark the 50th anniversary Musica Ellettronica Viva. This included performances at National Sawdust in Brooklyn, and the Big Ears Festival, Knoxville, Tenn. Symphony No. 2 was also released by the group. 106. Teitelbaum’s music was cerebral, but his sensory experience was the core of his work. He recalls the original performance “Organ Music” which included Lacy’s brainwaves as well as Aebi’s heartbeats in a paper entitled “In Tune. Some Early Experiments In Biofeedback Music (1966-1974)”. He described the concert in Milan as taking place in an auditorium with speakers around the audience. “One felt as though one was in the midst a shifting storm bio-electrical activity,” and said it was similar to feeling inside a human heart or brain. From www.npr.org