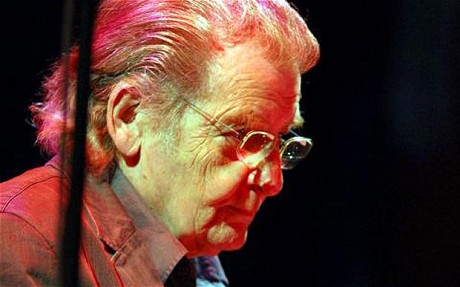

Stan Tracey, who died in 2013 at the age of 86, was Britain’s greatest and most original jazz composer. He was also a pianist with rare distinction whose work earned him praise from many of the best jazz musicians. Sonny Rollins asked: “Does anybody here realize just how great he is?” Tracey was completely self-taught as an artist, but his style was immediately recognisable. It was influenced by Thelonius Monk and Duke Ellington, but it is rooted in a deep vein that carries lyricism, which is only partially hidden beneath a hard, knotty surface. He composed music not for instruments, but for individuals players like his mentors. His work brought out the best of many generations of jazz musicians. Stanley William Tracey, the son of a bartender in a nightclub, was born in south London on 30 December 1926. He refused to leave school with his fellow classmates and ended his formal education at 12 years old. Although the family didn’t have a radio or gramophone at the time, the boy spent hours on the communal stairs listening to music from the neighbor upstairs. He learned to play the piano and won many talent contests. He joined an Ensa concert group at 16 and stayed with them until he was conscripted to the RAF. He joined the RAF Gang Show with Peter Sellers, Tony Hancock and became a member. He learned to play the piano and his first civilian job as an accompanist was that of Bob Monkhouse. Tracey briefly appears as a nightclub pianist, in the 1954 film I Am a Camera. Tracey was now captivated with jazz. He worked on the Queen Mary and Caronia transatlantic liners as a dance band member, which allowed him to hear the finest players live. In New York, he also heard Ellington and Monk for the first times. Modern jazz was almost impossible to sustain a livelihood in Britain during 1950s. Tracey joined dance bands of Roy Fox and Ted Heath. Although Ted Heath and His Music were Britain’s most popular big band, Tracey was disappointed by its dull repertoire. To make the music more lively, he would add a “Monkish” dissonance to the piano parts. He later said that Ted had never noticed. “Fortunately, he wasn’t very deaf.” Tracey took up the vibraphone while with Heath and played occasional feature numbers. In 1959, Tracey left Heath and formed a sextet, the MJ6 with Tony Crombie. They also recorded their own album. The album, Little Klunk, featured eight original compositions by Tracey and Kenny Napper, as well as Phil Seamen, the drummer. Ronnie Scott opened a jazz club in Soho that year, and Tracey was appointed its house pianist. He was a regular companion to some of the most prominent names in jazz, including Stan Getz, Wes Montgomery and Sonny Rollins, over the seven years he held this post. Tracey was not intimidated by these great musicians. Instead, he would challenge them with unexpected harmonies and interjections. Rollins loved it, while others didn’t. Scott supported Tracey loyally and he stood firm. Tracey’s tenure at Scott’s was when he wrote Under Milk Wood, his most well-known composition. It is an eight-part suite that Tracey based on Dylan Thomas’s radio drama. Much of the piece was written while he was returning from Scott’s by night bus to Streatham. It was recorded in 1965 and quickly became a classic in British jazz. Its success can be attributed to Tracey’s empathy with Bobby Wellins, the tenor-saxophonist. His hauntingly beautiful tone gives a touch of melancholy even to the most energetic sections. Under Milk Wood created a British-specific genre of jazz compositions that draw their inspiration from literary subjects. Tracey continued the tradition with Alice In Jazzland (1966), Seven Ages of Man ( 1969), The Poets’ Suite (1984), and many other. He worked with Rollins in 1966 on the music for Alfie. Tracey quit the club in 1967 after becoming exhausted by the non-stop challenge and long hours he had to work at Ronnie Scotts. This was a difficult time for British jazz. Many of its original audience were moving to “progressive” rock. He was losing work and even considered becoming a postal worker, but his wife Jackie, who is a tireless entrepreneur, helped him to survive on grants, teaching, and self-promoted events. A reenergized Tracey celebrated his 30th year in music in 1973 with a sold out concert at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall. The following year, he formed a quartet together with Art Themen, a partnership that would last 22 years. His own record label Steam Records was also established and he embarked upon a busy programme of work. He recorded and performed in all contexts, including solo piano and full 17-piece jazz orchestra. His most notable compositions include Genesis (1987), Portraits Plus (1992, nominated for the Mercury Prize) as well as Solo/Trio (1997). In 1999, his performances of Duke Ellington’s music with his big-band were widely acclaimed as Britain’s most significant contribution to Ellington’s centenary year. Tracey was awarded an OBE in 1986 for his contributions to British jazz. However, he joked that it was for 40 years of “battling bad pianos”. In 2008, he was promoted to CBE. His playing career took him to 39 countries, according to his own estimation. The Flying Pig, his final album was released in early 2009. It was inspired by a trip to the Battle of Loos where his father had been wounded, captured and executed in 1915. Stan Tracey’s widow Jackie died in 2009. He is survived by Clark Tracey, his son and drummer. His daughter predeceased him last Christmas. Stan Tracey, born December 30 1926, died December 6 2013. from http://www.telegraph.co.uk